Reframing how self-help tools support vulnerable users

A research-led redesign of a self-help app for girls and young women. The project examines why support tools often fail in moments of emotional distress, and how design can reduce cognitive load when users need help the most. Resulting in a clearer support model, design guidelines, and a suggested interface direction.

A bit of back story...

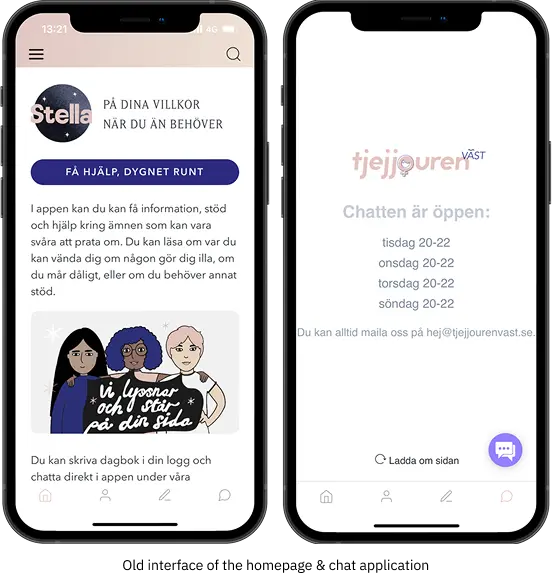

Stella is a self-help app developed with Tjejjouren Väst, a Swedish non-profit supporting girls and young women aged 10–25 through anonymous chat and resources around mental health, safety, and emotional distress.

Unlike typical wellness apps, Stella is used in high-risk, emotionally sensitive moments, where clarity, trust, and low cognitive effort are critical.

Despite being downloaded over 2,300 times, the app saw almost no active use. Sessions were brief (often under 30 seconds), and users rarely returned, indicating that while support existed, it wasn’t accessible when users needed it most.

This project set out to understand why the app failed in moments of vulnerability, and how support tools should be designed for emotional overload rather than ideal conditions.

Self-help tools fail users in moments of emotional distress

Girls and young women often seek self-help support during moments of vulnerability, anxiety, panic, or emotional overload. While many tools offer helpful content, users frequently struggle to access that support when their cognitive capacity is lowest.

This raises a critical question: Why do self-help tools that work in theory fail in the moments they’re needed most?

A self-help app that understands the users

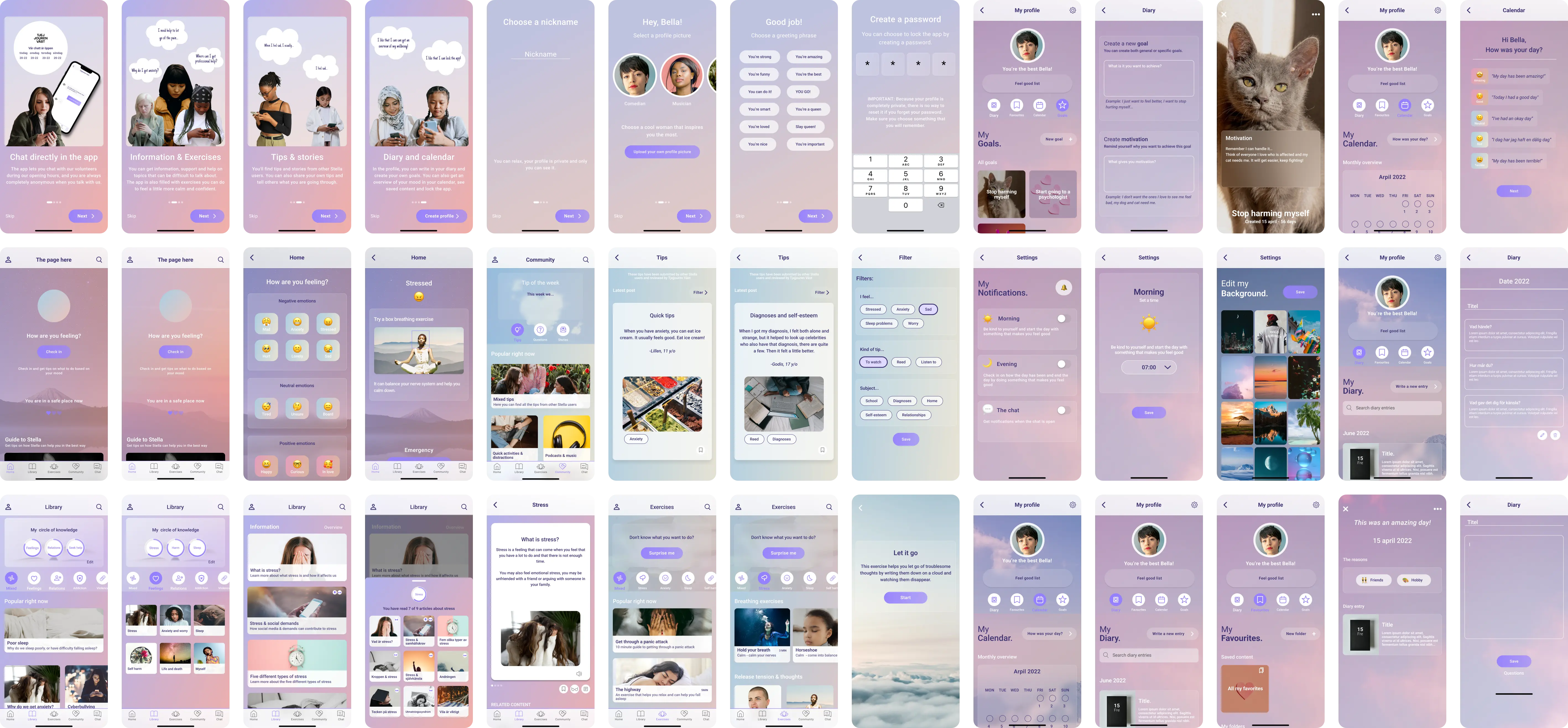

The final solution is a redesigned mobile app that adapts to when and how users seek support. Instead of treating all content as equally accessible at all times, the experience responds to users’ emotional state, cognitive capacity, and motivation, both in the moment and over time.

Final deliverables (at a glance)

- New information architecture and user flows

- Design guidelines grounded in user insight

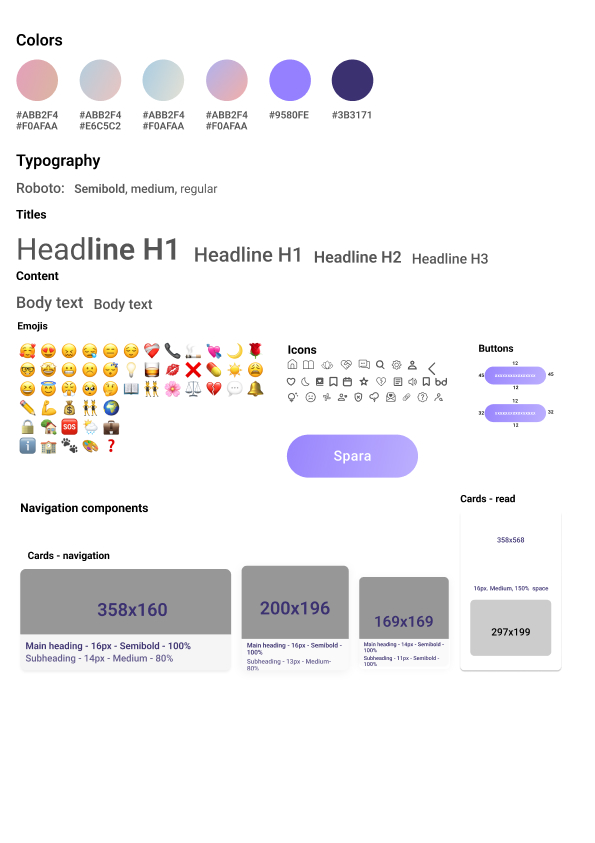

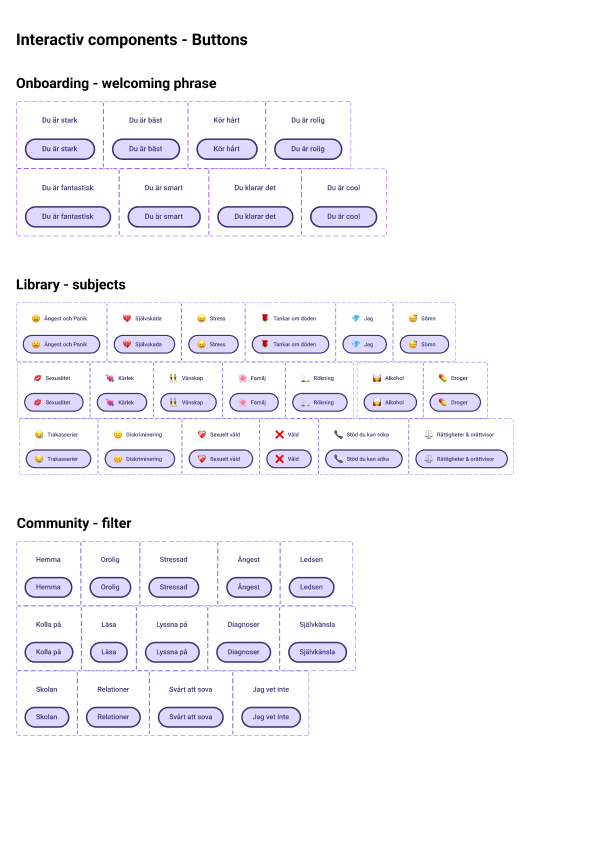

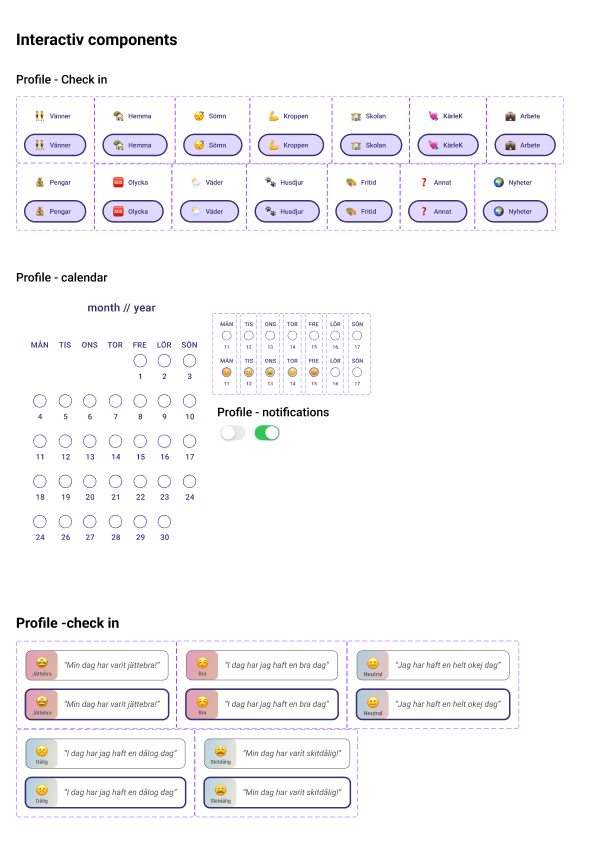

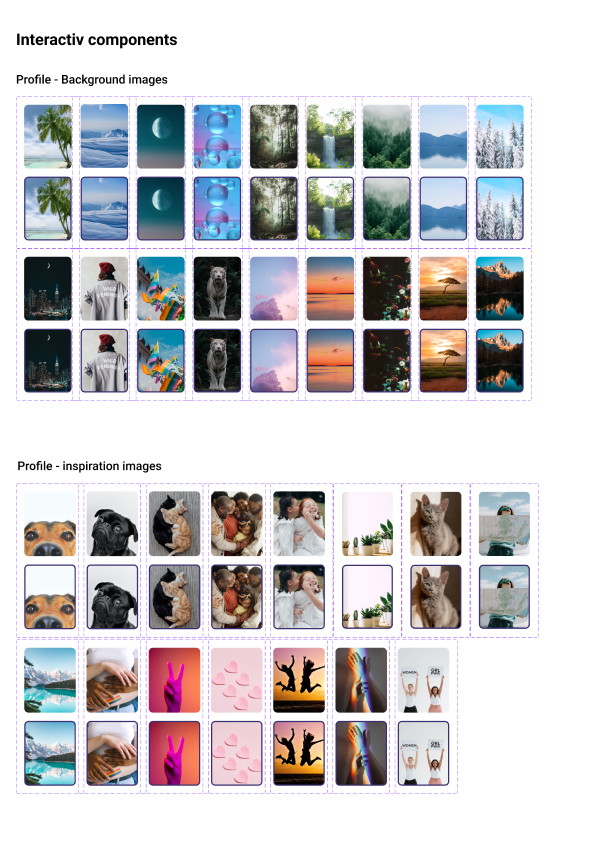

- UI style guide and component system

- High-fidelity prototype illustrating key use cases

- Validated interaction patterns for in-the-moment and over-time support

Solving overload, hesitation, and unclear next steps

The new structure is built around progressive disclosure and clear entry points, making it easier to act when capacity is low and reflect when capacity is higher.

- Fewer choices upfront, deeper content revealed gradually

- Clear “next step” without forcing commitment

- Easy re-entry without penalty or loss of context

Reducing cognitive load when decision-making is hard

- Immediate check-in on the homepage

- One suggested action instead of multiple choices

- Randomized exercise option when choosing feels overwhelming

Helping users reflect, find patterns, and build continuity

- Goal setting and gentle motivation without pressure

- Calendar and mood tracking to identify patterns over time

- Support for understanding why certain days are harder or easier

- Signals for when professional help may be beneficial after repeated difficult periods

Supporting long-term iteration in a high-risk context

Given the sensitivity of the domain, the final outcome prioritizes guidance over prescription.

- Design guidelines grounded in user research

- Principles for reducing guilt, pressure, and emotional friction

- Requirements for safe disengagement and perceived control

- A framework that future teams can build on without re-introducing harm

These guidelines ensure that future features and changes remain aligned with user needs, even as the product grows.

Understanding why support failed when users needed it most

The research phase focused on understanding how girls and young women actually experience self-help tools, emotionally, cognitively, and over time.

The goal was not only to identify usability issues, but to uncover patterns in how support is sought, avoided, or abandoned. This allowed me to observe both what users said and what actually happened when they tried to use the product.

Participants:

- 100+ girls and young women

- Ages 10–25

- Current-users

- New-users

Methods:

- White paper research

- Surneys

- Competitive analysis

- In-depth interviews

- Usability testing and guided walkthroughs of the existing app

Making sense of what was actually happening

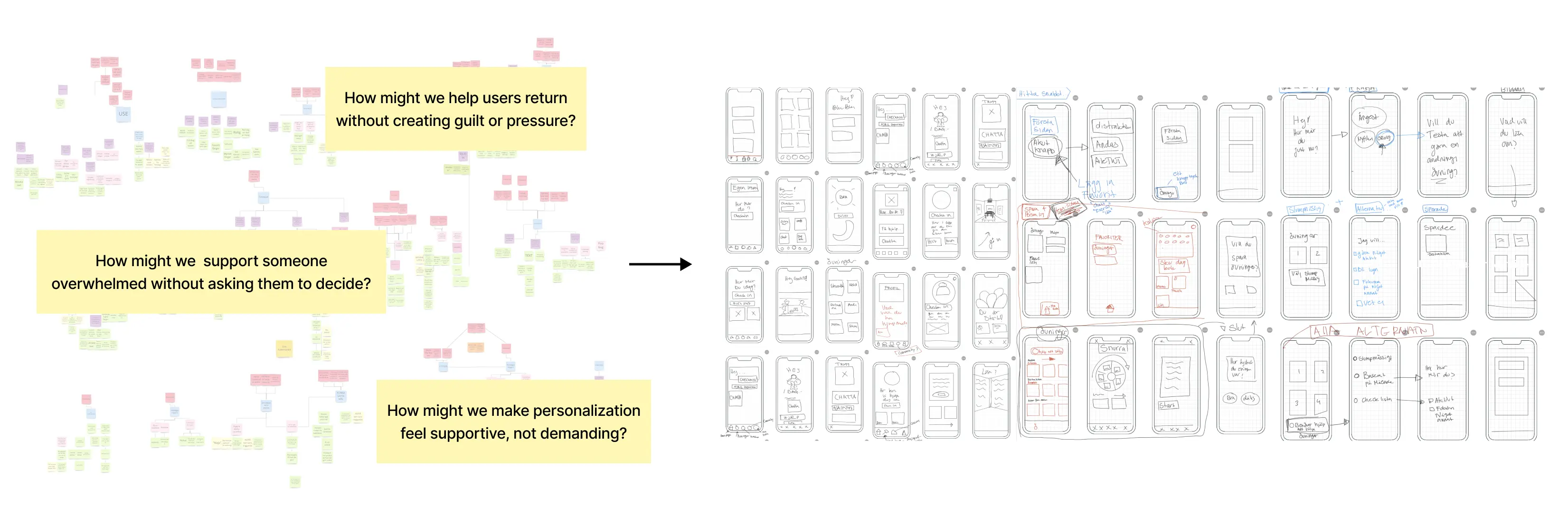

I synthesized all qualitative data through affinity mapping, clustering observations, behaviors, quotes, and emotional responses from interviews, surveys, and usability walkthroughs. In total, this resulted in over 2,000 individual data points, which made prioritization and trade-offs a critical part of the work.

several patterns stood out

Safety kept coming up as the most important thing

Not just technical security, but emotional safety, anonymity, tone, and a sense of control.

Motivation was closely tied to feeling understood

Users were motivated by seeing others’ experiences and by being able to shape the app around their own needs.

Personalization mattered more than I expected

Being able to save, organize, and return to content increased trust and made the app feel more personal and less clinical.

Usability issues directly killed motivation

Confusion (“Where do I start?”), hidden content (“I didn’t know there were exercises”), and long blocks of text often led to immediate disengagement.

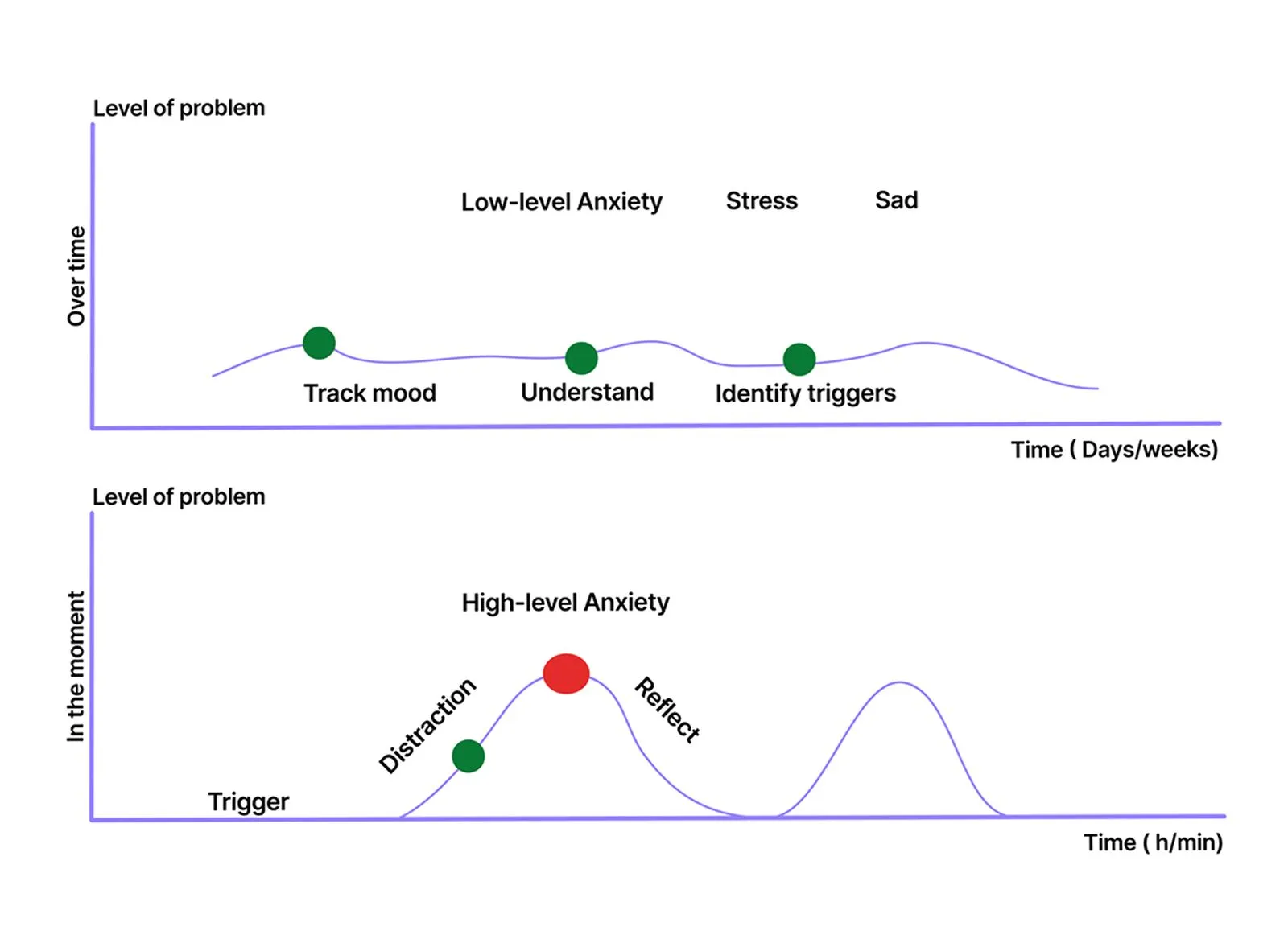

The Two Support Needs: A turning point in the project

Another thing that that stood out in the synthesis was the two diffrent moments where user might seek support:

In-the-moment support

- Users felt overwhelmed and unable to make decisions

- They needed immediate clarity, emotional grounding, and very low cognitive effort

In-the-moment support

- Users were calmer and more reflective

- They needed tools to understand patterns, build motivation, and make sense of recurring emotions

This distinction shaped the product strategy: the product needed to adapt its level of guidance, structure, and effort depending on when and why a user engaged.

What This Led To

This synthesis changed the direction of the project, and I asked myself:

How can support adapt to a user’s emotional state and motivation, without overwhelming or pressuring them?

That question became the foundation for the two-mode support model, the new information architecture, and the design guidelines that followed.

What if the real problem isn't the app, it's the system?

Initial ideation went big: What if we redesigned the entire healthcare pathway? The research was clear... users needed better access to care, not just a better app. Early concepts explored: AR/VR support experiences, direct healthcare system integration, and service design that bridges self-help and professional care.

Through stakeholder meetings, I quickly realized that even if some of the problems should be solved at a system level, this project needed to focus only on what could be achieved within a mobile app.

This phase shaped the first set of low-fidelity concepts and clarified which ideas were worth taking forward.

Iterating Early Concepts Through User Feedback

As ideas started taking shape, I tested early concepts through lightweight walkthroughs and feedback sessions. Testing these ideas surfaced important trade-offs that shaped the final direction.

This was an interactive prototype, and tested on mobile devices by five potential users aged 16–20.

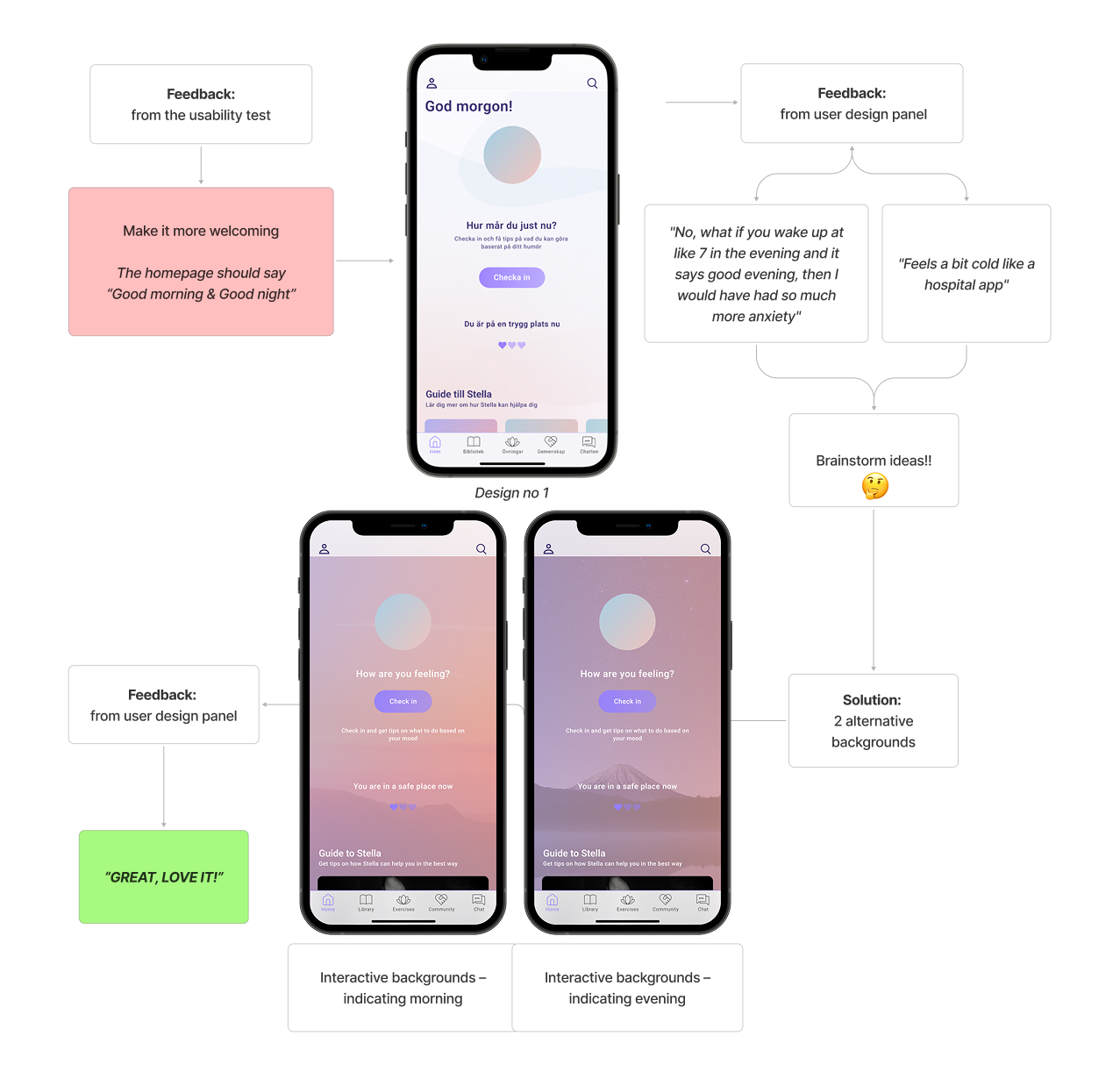

Below are three examples where user feedback directly shaped the direction of the high-fidelity design.

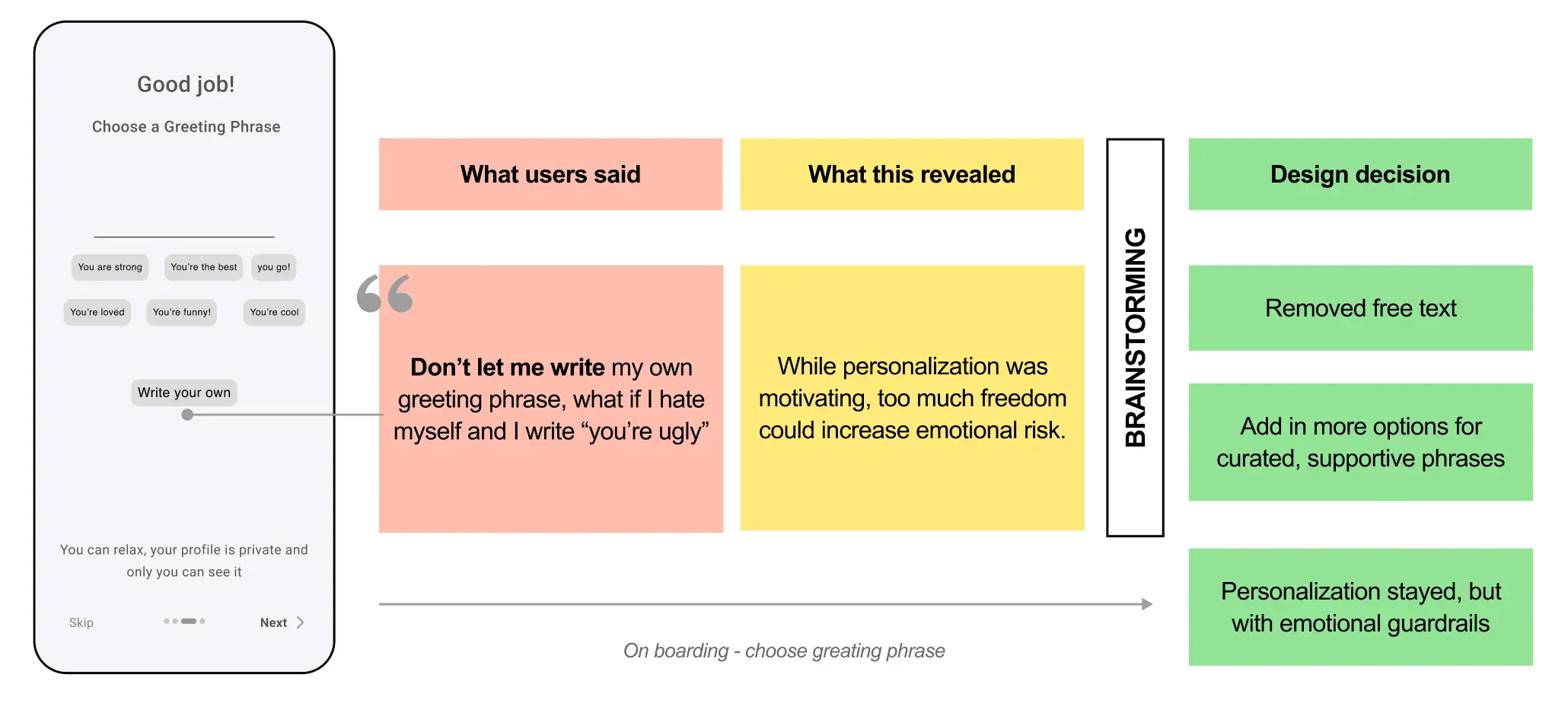

Personalization Needs Structure, Not Unlimited Freedom

Insight: Users want personalization and to feel seen

Initial idea: Let users write their own greeting phrase during onboarding

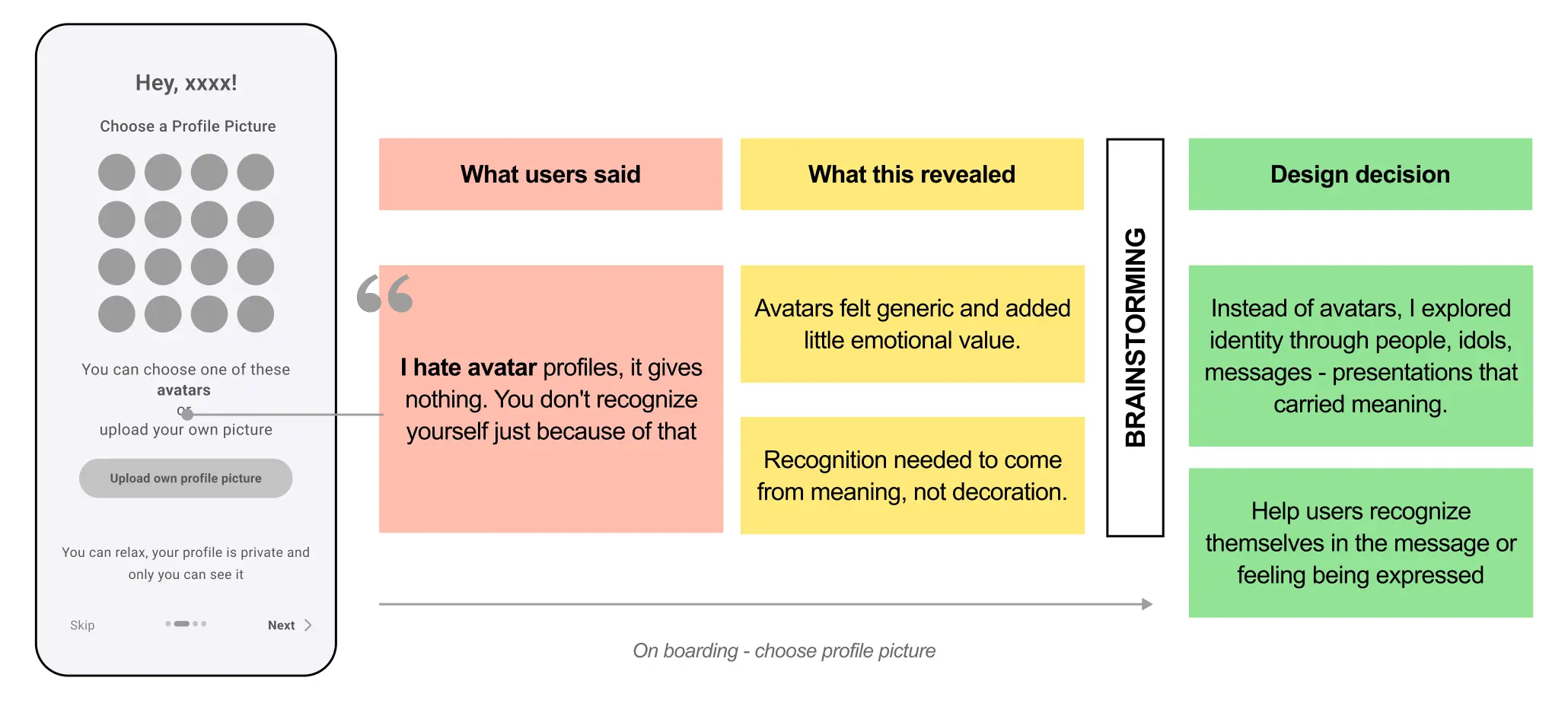

Identity Should Feel Meaningful, Not Generic

Insight: Users want to recognize themselves in the app

Initial idea: Avatars during onboarding to increase identification

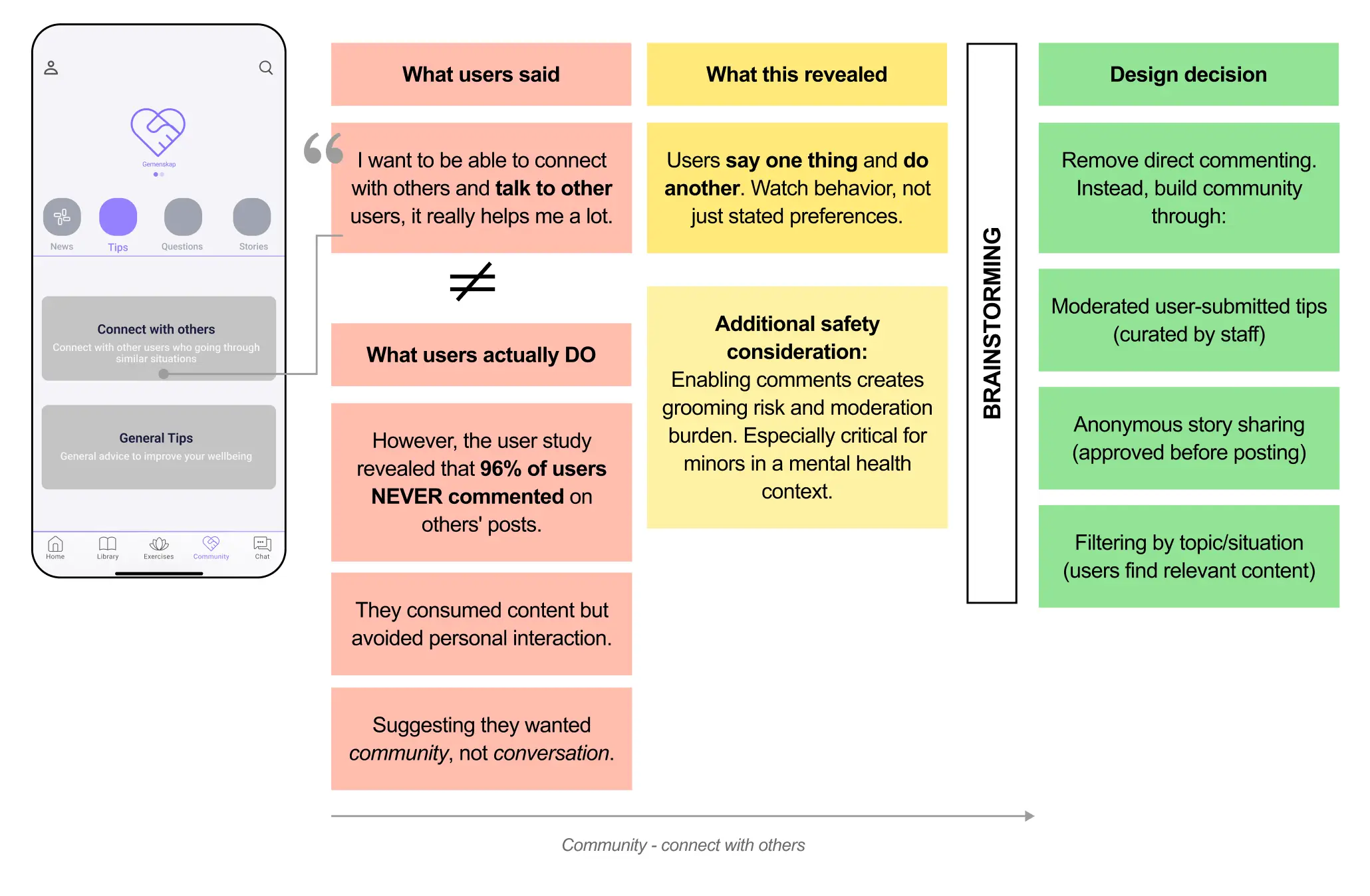

Community Requires Safety Over Expression

Insight: Support can come from others in similar situations

Initial idea: Enable comments to talk to and support others

Designing with users, not assumptions

After iterating on structure, flows, and low-fidelity concepts, I moved into high-fidelity design. To ground the visual and interaction decisions, I created a small user design panel and used it continuously throughout this phase.

How it worked

- 7 participants

- Ages 16–18

- Used for quick feedback loops and lightweight A/B testing

- Compared alternatives for layouts, tone, colors, icons, imagery, and micro-interactions

Below is an example demonstrating how user feedback and design trade-offs shaped the final interface, specifically, the home screen design and messaging.

The Solution

The final solution is a redesigned mobile app that adapts to when and how users seek support. Instead of treating all content as equally accessible at all times, the experience responds to users’ emotional state, cognitive capacity, and motivation, both in the moment and over time.

The result is a system that feels:

- Safe when users are overwhelmed

- Supportive without pressure

- Personal enough to motivate return use

What was delivered:

- A new information architecture and user flow

- A two-mode support model (in-the-moment + over-time)

- A cohesive interface and design system

- Clear design guidelines to support future development

PS: All copy was translated from Swedish to English to better communicate the concept to an international audience. The translation is not always 1:1, which resulted in some alignment inconsistencies in the final design.

Two Support Needs, One Coherent System

Research showed users weren’t failing to engage because of missing features, they were seeking support in fundamentally different emotional states.

The solution is built around two complementary modes of support:

In-the-moment support

For users who are overwhelmed, anxious, or unable to decide.

- Minimal choices

- Clear next step

- Emotional grounding of information

- Randomized or guided actions to reduce decision fatigue

Primary surfaces

- Homepage check-in

- “Surprise me” exercise

- Emergency access is always visible

Over-time support

For users who are calmer and able to reflect.

- Progress tracking

- Emotional pattern recognition

- Motivation through meaning and personalization

- Gentle nudges toward help when needed

Primary surfaces

- Calendar & mood history

- Diary & saved content

- Goals and reflections

- Positive notification

User flow & Informational Architect

The original app exposed all content at once, increasing overload and hesitation. The redesigned architecture uses progressive disclosure and clear entry points.

Key structural decisions

- Fewer choices upfront, deeper content revealed gradually

- Navigation aligned with users’ mental models

- Easy re-entry without loss of context or progress

Design System & Guidelines

The design system provides clear direction for what should be included and how it should be designed, ensuring consistency across the app’s features, visuals, and interactions.

Final Usability Test: Validating the Direction

A final usability test was conducted on the high-fidelity prototype to evaluate whether the redesigned experience successfully supported users in both vulnerable moments and over time.

Test setup:

- 8 participants

- Ages 11–20

- In-person, mobile-based testing

- 30–90 minutes per session

- Task-based walkthroughs with follow-up questions

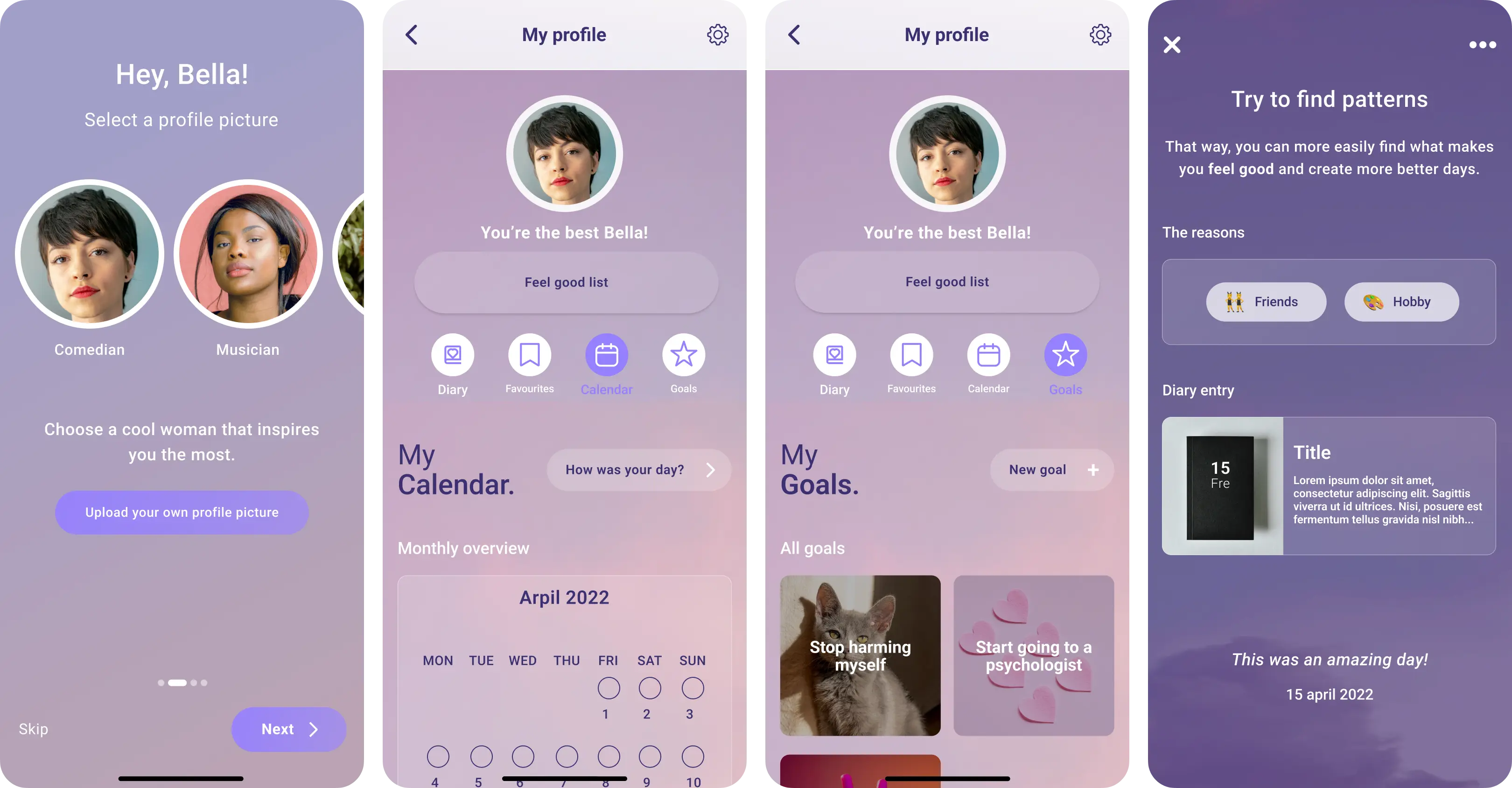

Reducing overload and hesitation at the first touchpoint

What I was testing

Whether onboarding could build trust and relevance quickly, while keeping emotional effort low.

Design focus

- Onboarding that clearly communicates purpose and safety

- Personalization through real people and role models to create recognition and inspiration

- Password protection to support privacy and emotional safety

What users told me

Participants described the onboarding as clear, light, and engaging.

Seeing real people and role models made the experience feel more meaningful and relatable than generic avatars, without requiring users to expose themselves or make difficult choices.

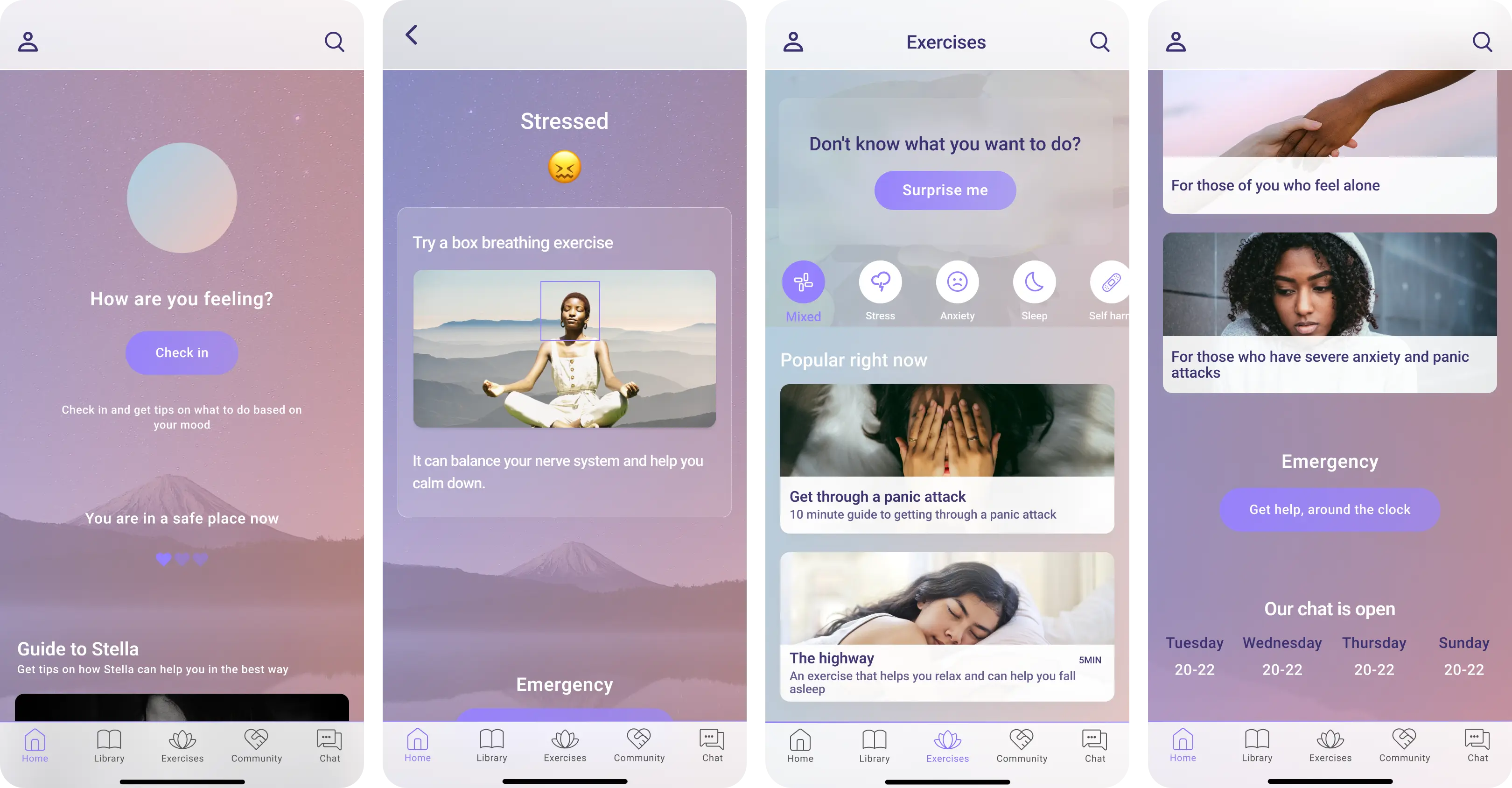

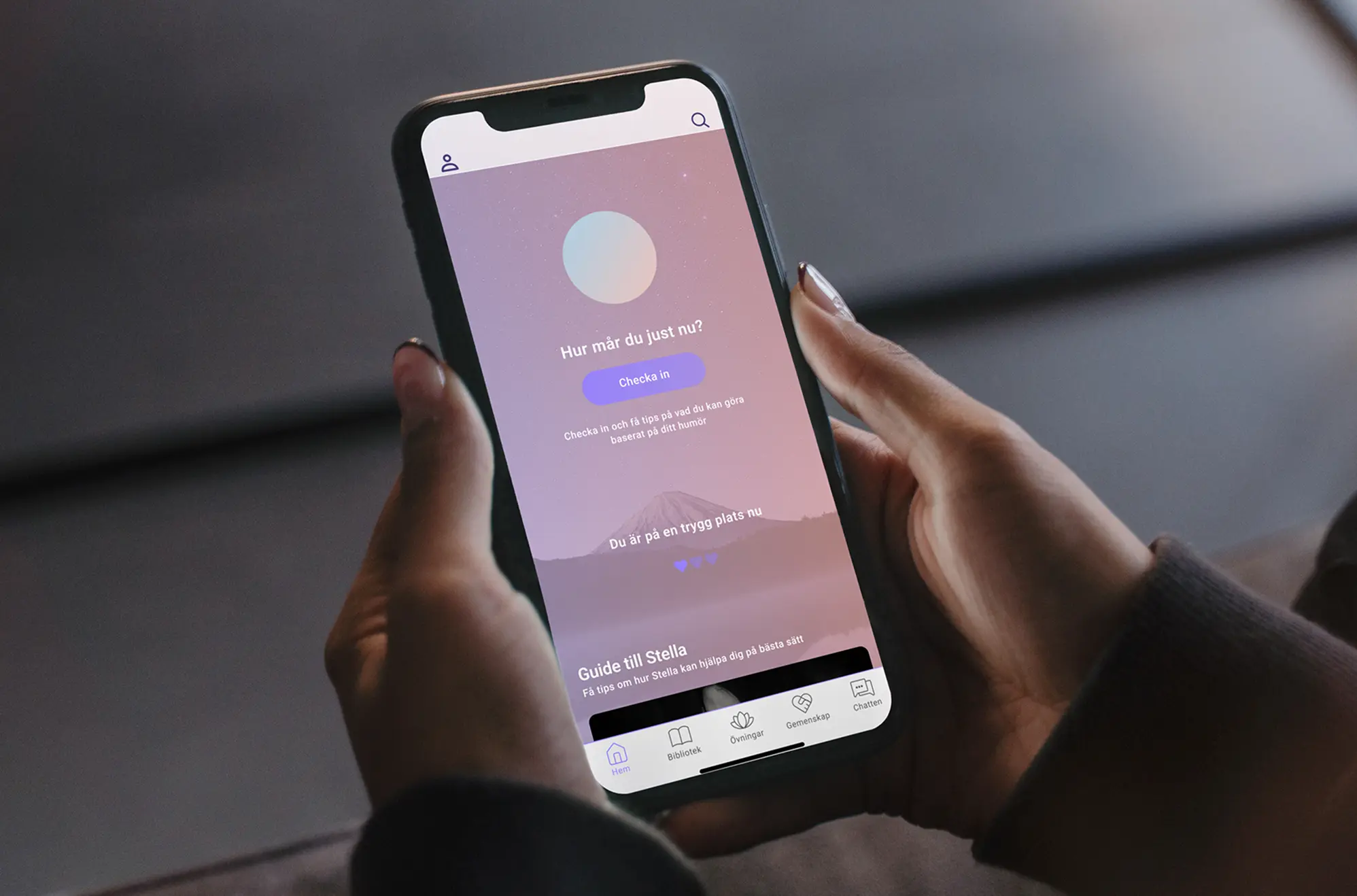

Supporting users in moments of vulnerability

What I was testing

Whether the homepage could feel welcoming and emotionally supportive, while helping users know how to begin during moments of stress or overload.

Design focus

- A warmer, more calm homepage

- Reduced text and clearer visual hierarchy to lower cognitive load

- Immediate check-in on the homepage to guide users

- Navigation patterns and labels aligned with users’ mental models

What users told me

The homepage felt calm, welcoming, and easier to understand.

Users knew where to start without feeling pressured, and the check-in helped them move forward without having to think too much.

Supporting reflection and learning over time

What I was testing

Whether educational content could stay accessible and motivating over time — without becoming overwhelming or demanding, especially when users return in different emotional states.

Design focus

- A feed-based structure that surfaces relevant content without requiring search or planning

- Bite-sized, swipeable articles to reduce cognitive load

- Multiple ways to engage (read, listen, save) depending on capacity and preference

- Progress visibility to support motivation without pressure

What users told us

The Library felt usable and easy to return to.

Users understood how to save content, pick up where they left off, and track what they had already explored, without feeling overwhelmed.

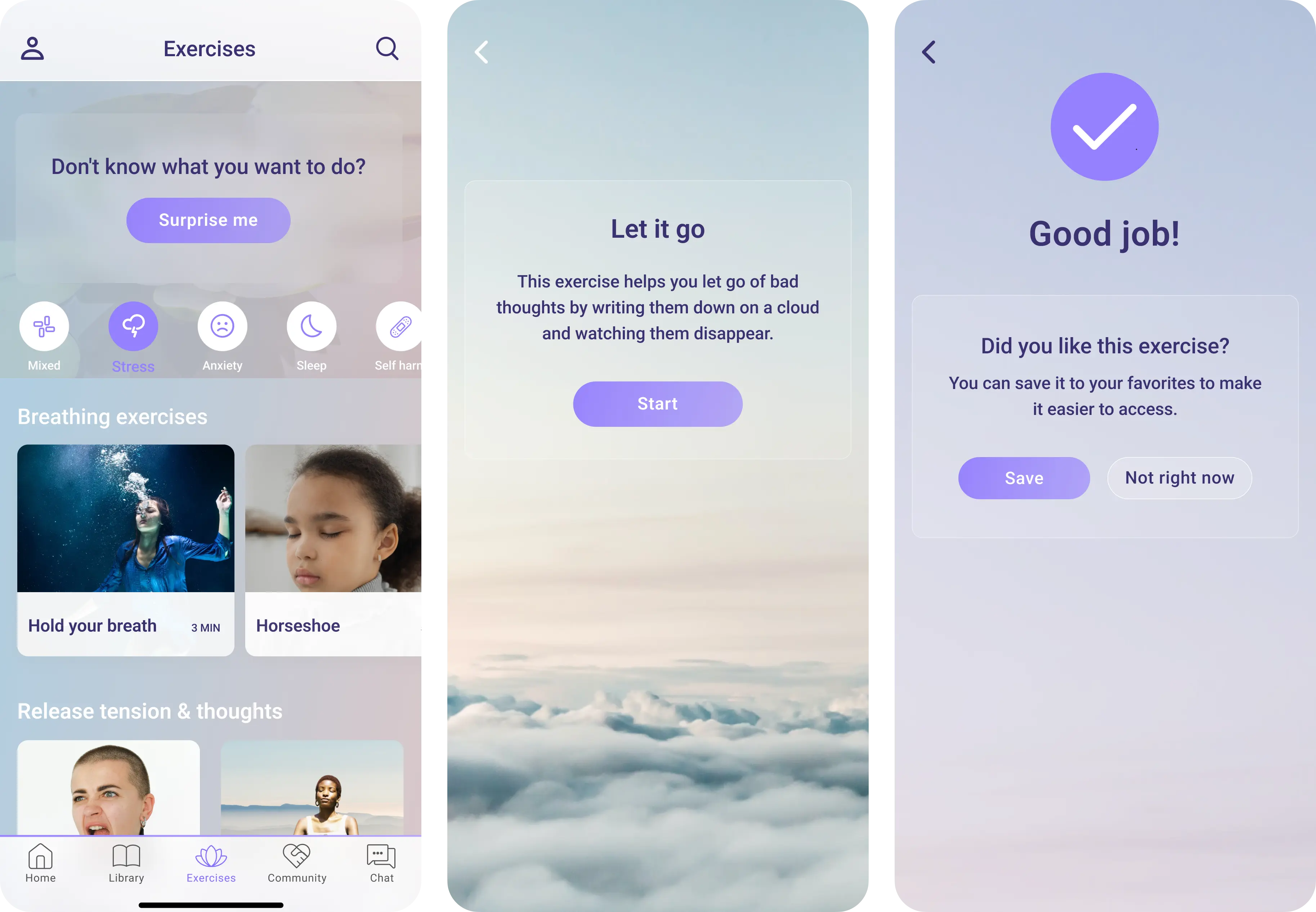

Reducing decision fatigue while supporting regulation over time

What I was testing

Whether users could start an exercise quickly during moments of stress, and still return to exercises over time without feeling bored, pressured, or overwhelmed.

Design focus

- A feed-based structure that mirrors the Library for familiarity and ease

- Clear start and end points to create a sense of completion

- Short, interactive exercises using visuals and limited text

- A randomized “Surprise Me” option to remove decision-making when capacity is low

What users told me

They found the exercises more engaging, easier to complete, and especially valued the random option on harder days when thinking felt difficult.

Supporting motivation and connection without compromising safety

What I was testing

Whether connection with others could increase motivation and a sense of belonging, while remaining safe, moderated, and appropriate for a vulnerable user group.

Design focus

- Community structured around shared experiences, not direct messaging

- Moderated content to reduce risk and maintain trust

- Tips, stories, and Q&A to support both in-the-moment reassurance and over-time motivation

- Light identity cues (name and age) to increase relatability without exposing users

- Recurring content (weekly tips) to encourage return visits

What users told us

The Community felt meaningful and safe. Seeing names and ages made stories feel more personal and relatable, without making users feel exposed. Participants described the Community as an important and motivating part of the experience over time.

Supporting ownership, reflection, and motivation over time

What I was testing

Whether long-term support features could feel personal and motivating, without becoming heavy, demanding, or easy to abandon.

Design focus

- A single profile space that brings together reflection, tracking, and personalization

- Quick access to saved content for in-the-moment support

- Calendar-based reflection to help users notice patterns over time

- Motivation through gentle reinforcement, not pressure or streaks

- Personalization that makes the app feel theirs, without extra effort

What users told me

Being able to save content into folders, reflect on patterns in the calendar, and adjust visuals and notifications helped users feel ownership, and supported both quick relief and longer-term growth.

When asked whether they would use the app or recommend it to a friend, every participant said yes.

“YES ! I need this, and I want it now.”

Designing support that adapts, not demands

The problem we set out to solve:

How can a self-help system support girls and young women in moments of vulnerability, without overwhelming, pressuring, or asking too much of them?

Throughout the research, it became clear that many self-help tools fail not because they lack content, but because they assume users have the cognitive capacity to engage when they often don’t. Moments of anxiety, panic, or emotional overload require a fundamentally different kind of design.

This project reframed the challenge from what features are missing to how support should appear, guide, and recede depending on a user’s state and motivation.

Reflections & next steps

Looking back, there are interface-level details I would refine today, such as tighter visual hierarchy in some views, clearer CTA emphasis in specific flows, and more consistent spacing and alignment in high-density screens.

However, this work was intentionally positioned as a directional foundation, not a locked final product. The redesigned app that followed was built on these principles, structures, and insights.

What mattered most, and still holds, is the underlying approach:

designing for emotional context, cognitive load, and motivation, and letting user behavior (not assumptions) guide every decision.

Final reflection

This project shaped how I think about UX at a systems level.

It taught me that meaningful design isn’t about adding more, but about knowing when to guide, when to step back, and how to support people when their capacity is lowest.

Working in a mental health context forced every decision to be intentional. Listening to users talk about vulnerability and trauma pushed me to design with care, restraint, and responsibility, especially around language, hierarchy, and choice.

More than anything, Stella clarified the kind of work I want to do: design that adapts to people, not the other way around.

Final thoughts:

The wellbeing of girls and young women must be a priority, not just in design, but in the healthcare system as a whole. It's not enough to provide basic functionality or surface-level support. They deserve real care, real tools, and a system that meets them where they are. Something more than just functional. Something meaningful.